Everything you need to know about that probate is, how the probate process works, how long it takes, costs, executor duties, and state differences.

Losing someone you love is hard enough. If you’re asking yourself “What is probate?” and you’re tired of googling, you’re in the right place. With this guide, you’ll understand how the probate process works, how long it typically takes, what it costs, and the steps that executors follow. You’ll also find specific state questions, cases, and answers to the questions families ask most.

Probate is the court-supervised legal process that oversees the management and transfer of a deceased person’s estate.

Its main goal is to make sure that everything the person owned is properly collected, valued, and distributed according to the law.

Probate does not open automatically when someone dies. According to the American Bar Association, the probate process begins when someone files a petition with the probate court. Once the petition is submitted, the court reviews the will, if there is one, and formally appoints an executor or personal representative to manage the estate.

.png)

If the person left a will, the court confirms that the document is valid and appoints the person named as executor to carry out its instructions. If there is no will, the court assigns an administrator to manage the estate under state inheritance laws.

Probate involves several responsibilities, such as:

The process provides legal protection for everyone involved: beneficiaries receive what they are owed, and executors or administrators are shielded from personal liability if they follow court rules.

In some states, small or uncomplicated estates can qualify for simplified procedures, allowing the executor to skip formal hearings or use affidavits instead of full filings. However, larger or contested estates almost always go through formal probate.

Probate is usually required when the person who passed owned assets solely in their name and no beneficiary is listed.

You can often avoid probate when assets are set up to transfer automatically at death. Common ways include:

Assets titled only in the person’s name, with no beneficiary or survivorship, generally do require probate.

For example: In many states, including New York, small estate or “voluntary administration” procedures are only available when the estate does not include real property titled solely in the decedent’s name. Real estate generally requires a full probate or administration case so that the court can legally transfer ownership. New York Courts: Small Estate / Voluntary

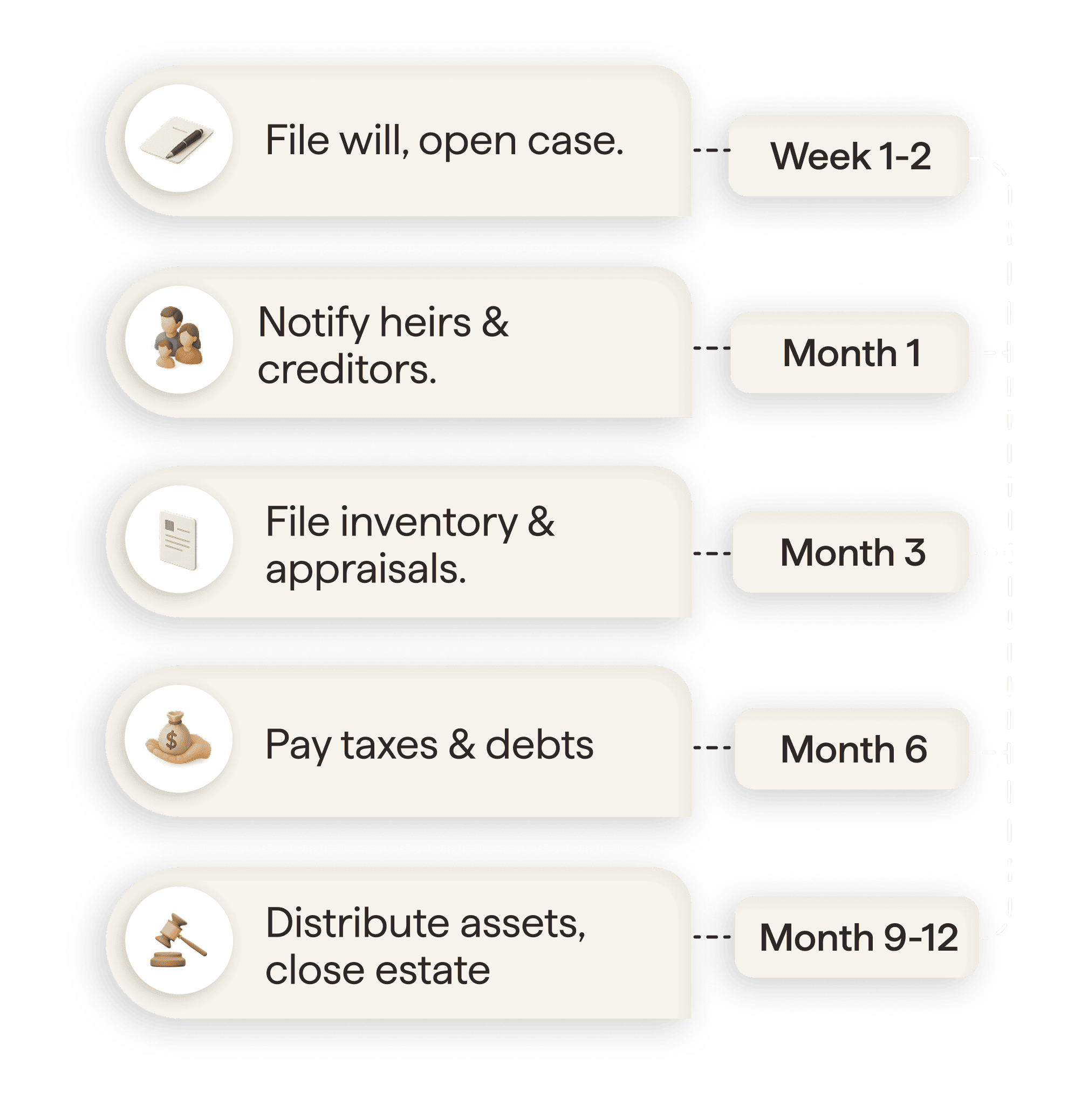

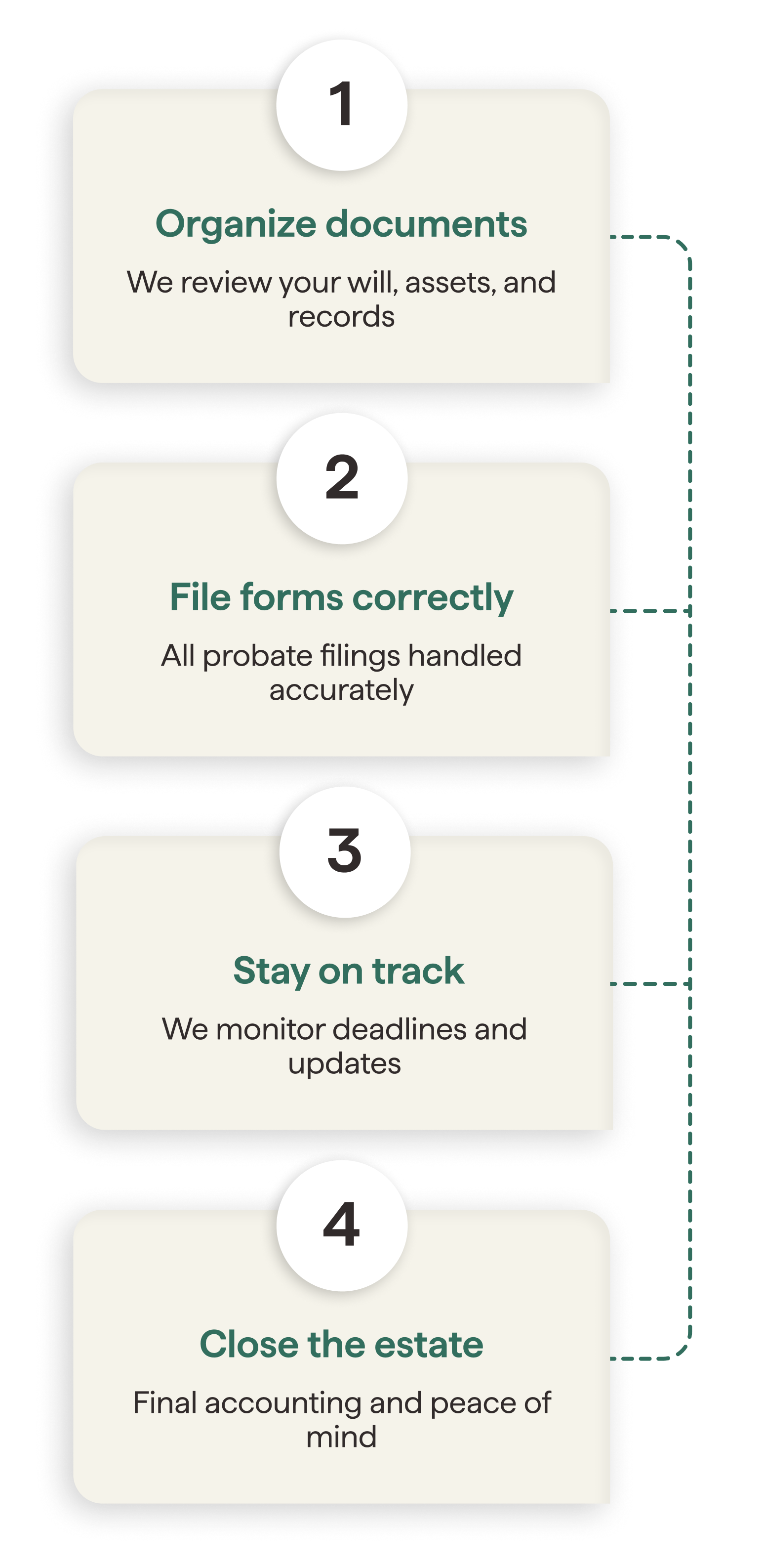

At a high level, the probate process follows these steps; forms and timing vary by state.

Submit the original will (if any) and certified death certificates to the probate court in the county where the decedent lived. The court opens a file and assigns a case number. Keep extra certified copies: banks and insurers will ask for them.

The executor named in the will (or an interested heir if no will) files a petition asking the court to start the case. If there’s no will, this is an administration case and the court appoints an administrator.

After appointment, the court issues Letters Testamentary (will) or Letters of Administration (no will). These documents give you legal power to act for the estate: open accounts, access records, sell assets with court approval if required.

Send required notices to heirs/beneficiaries and publish creditor notice if your state requires it. Track claim deadlines; late or missed notices can trigger disputes and penalties.

Locate accounts and property, secure the home, forward mail, and order appraisals where needed. Create the inventory the court requires: cash, real estate, vehicles, personal property, securities, insurance, retirement accounts, and debts owed to the estate.

Review and pay timely creditor claims, expenses, and taxes. File the decedent’s final Form 1040 and, if the estate has income, Form 1041 (fiduciary return). Keep receipts, your final accounting must document every dollar.

After debts and taxes are cleared (and any required court approvals obtained), transfer property to the heirs per the will or state intestacy laws. Get receipts/releases from beneficiaries.

The Superior Court of California says that distribution rules vary by state. In some states, the personal representative can distribute assets after paying debts and taxes and before requesting to close the estate. In other states, the representative must petition the court for approval before distributing anything. Check your state’s probate rules or local court website for specific requirements.

Prepare a complete accounting of money in/out, provide it to beneficiaries (and the court if required), resolve objections, and request an order to close the estate. Keep records after closing in case of later questions.

As executor, you take on specific tax duties for the estate. See the IRS guidance for survivors, executors, and administrators for the full list and forms.

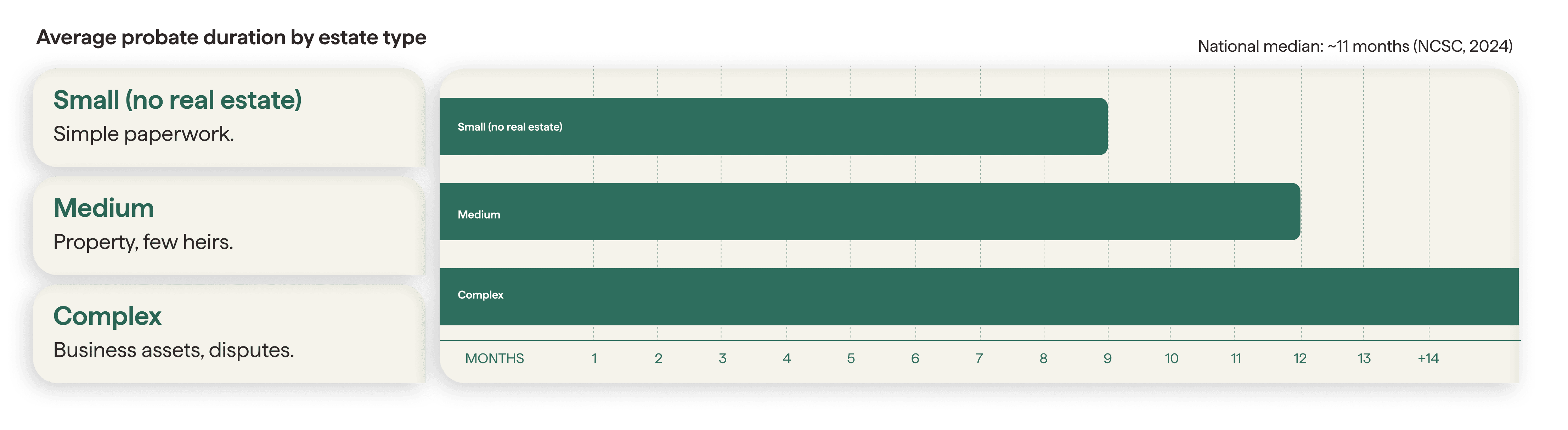

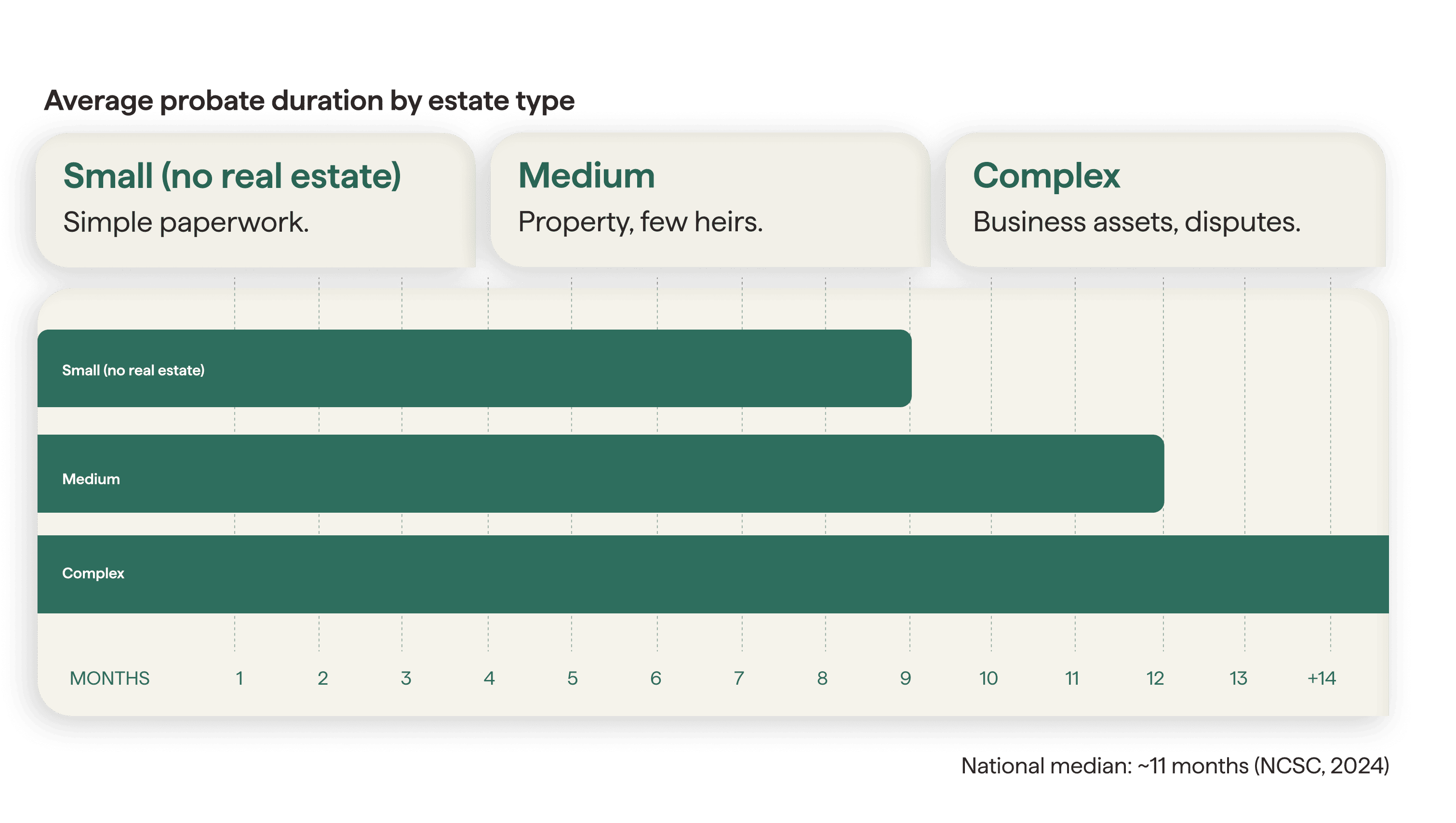

How long does Probate take on average?

Most probate cases take 9-12 months, but timelines vary with estate complexity, disputes, real-estate sales, tax filings, and local court backlogs.

The timeline depends on:

Note: Simple estates with no disputes can finish in 6-9 months. Complex estates with property sales, debt, or tax filings can exceed 18 months. Common causes of delay include missing documents, disputes among beneficiaries, and difficulty locating assets or heirs.

Executors can check timeline averages on each state through the National Center for State Courts.

How much does Probate cost? And who pays?

Probate costs typically range from 3% to 7% of the estate’s total value, depending on attorney fees, court filings, and appraisal requirements.

Common probate costs include:

Q: Who pays probate costs?

A: All probate expenses are paid from the estate before any assets are distributed to heirs.

.png)

| Category | Traditional law firm | Alix |

|---|---|---|

| Billing structure | Hourly rates or percentage of the estate | Transparent flat fee agreed upfront |

| Scope of service | Legal representation only | Full-service support including filings, coordination, and communication |

| Typical challenges | Fees can increase with delays or disputes | Predictable pricing regardless of case duration |

| Communication | Varies by firm; may bill for updates | Dedicated Care Team with ongoing communication |

| Process management | Handled separately by lawyers and executors | Centralized system that keeps everything on track |

| Client experience | Complex and time-consuming | Simplified, guided, and efficient |

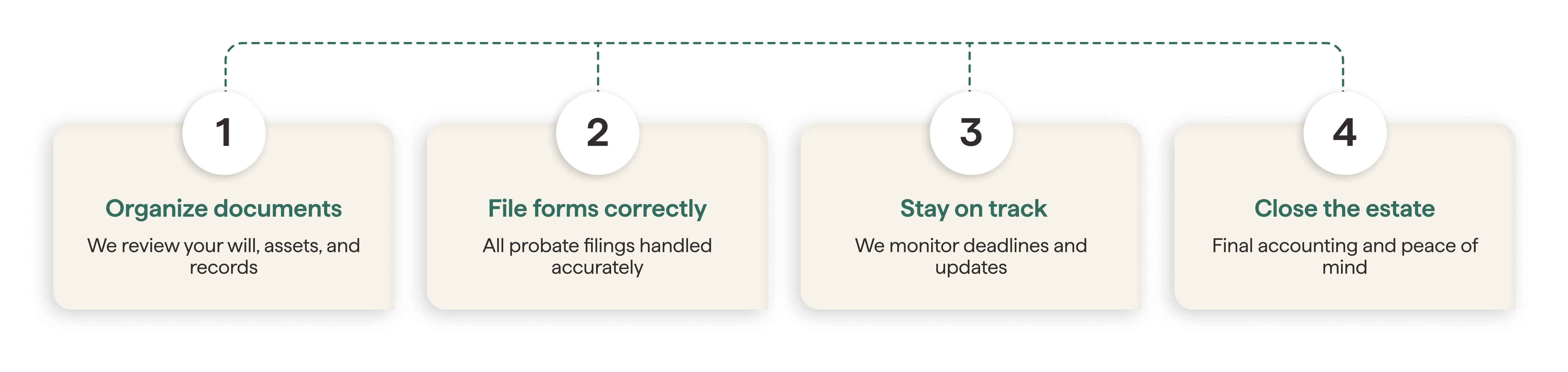

Probate runs smoothly when executors stay organized, timely, and transparent with beneficiaries.

While every estate follows the same general structure, executors often struggle with coordination and accuracy.

This section outlines how an organized approach keeps the process on track and reduces delays.

| Aspect | Why it matters | Best practice for executors |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation | Missing or incomplete forms are the most common reason for probate delays. | Create a checklist of required filings before the first court deadline. |

| Creditor management | Late or missed notices can lead to penalties or disputes. | Keep a log of creditor communications and maintain proof of notice publication. |

| Asset inventory | Courts require a verified inventory before distributions. | Gather account statements, property appraisals, and titles early in the process. |

| Tax filings | Estates may owe final income and fiduciary taxes. | Coordinate timelines for IRS Form 1041 and any state filings. |

| Communication | Beneficiary disputes usually arise from lack of information. | Provide periodic updates and keep written summaries of all key decisions. |

Executors can reference official guidance from the U.S. Government: After Death Resources.

Probate rules and filing fees vary across the U.S. While the core process is similar everywhere, timelines, forms, and court costs differ.

| State | Average duration | Court fee range |

|---|---|---|

| California | 9–18 months | $400–$1000 |

| Florida | 6–12 months | $300–$800 |

| Texas | 8–16 months | $300–$700 |

| New York | 9–15 months | $500–$900 |

| Illinois | 10–15 months | $300–$850 |

| Pennsylvania | 9–14 months | $300–$800 |

| Arizona | 6–10 months | $250–$600 |

| Ohio | 9–13 months | $250–$750 |

Sources:

Probate timelines vary widely depending on state laws, estate size, and the court’s workload. Always verify your local requirements through your state judiciary website before filing.

Executors can reference the National Center for State Courts Probate Data for nationwide statistics and trends.

Executors and families often share the same questions about probate timing, costs, and responsibilities. Below are concise answers drawn from official state and federal sources.

Q: Do I need a lawyer for probate?

Not always. Most states allow you to handle probate without hiring an attorney if the estate is straightforward, uncontested, and all heirs agree.

However, legal help can be useful when:

- The will is contested or unclear

- Real estate spans multiple states

- There are large debts or unpaid taxes

- Beneficiaries cannot be located

Some states, such as Florida, require attorney involvement for the probate process. Others, such as California, allow some executors or administrators to represent themselves without an attorney, known as “pro se” representation. Always confirm your state’s requirement through the local court or state bar association.

You can confirm your state’s rule on its judicial website or review the American Bar Association’s probate overview

Q: How long after death do you have to file probate?

Courts do not require probate to be filed within a specific number of days after death. However, many states recommend filing within one to three months so that bills can be paid, accounts can be accessed, and assets remain protected. Waiting too long can create complications, but there is usually no formal legal deadline unless stated in state law.

Some states simply require that the will be lodged with the court within a set time period. Always check local probate rules to confirm.

Q: What happens if there is no will?

When someone dies without a valid will, the estate goes through intestate probate.

If someone dies without a valid will, the court applies intestate succession laws, a legal formula that decides who inherits.

Usually:

1. Spouses and children inherit first

2. If none, parents or siblings inherit

3. More distant relatives only if no immediate family exists

The court appoints an administrator (often a family member) to handle everything a normal executor would-filings, debt payments, and distributions.

Q: Who pays probate fees and taxes?

All probate expenses, including court costs, filing fees, and professional services, are paid from the estate’s funds, not by the executor personally. Executors must keep accurate records of these transactions for the final accounting submitted to the court.

Q: Can probate be avoided altogether?

In some cases, yes. Assets held in joint ownership with rights of survivorship, trusts, or with named beneficiaries (like life insurance or retirement accounts) can bypass probate entirely. However, most estates still include at least a few assets that require court supervision to transfer legally.

Q: What are the main documents required to start probate?

Executors typically need:

1. The original signed will

2. Certified death certificates (2–5 copies)

3. A petition to open probate

4. A full asset inventory with approximate values.

5. Contact list of heirs and creditors.

Q: What can delay or complicate probate?

Delays usually come from:

- Missing or incorrect forms

- Disputes between heirs

- Hard-to-value assets (like property or business shares)

- Waiting on tax clearance or creditor deadlines

Q: Is probate the same in every state?

No. Probate procedures depend heavily on state law.

- California: long formal hearings and multiple filings

- Florida: simplified “summary administration” for small estates

- Texas: independent executors act with limited court oversight

- New York: detailed court supervision and higher filing fees

Most states require similar core steps: file will, notify creditors, pay debts, distribute assets, etc. Forms, deadlines, and costs differ.

Q: What taxes must be filed during probate?

Two main filings are required:

- Final personal income tax return (Form 1040) for the decedent, covering the year of death.

- Estate income tax return (Form 1041) if the estate earns income before distribution.

Some states also levy inheritance or estate taxes on assets passed to heirs.

Executors should check with a CPA or their state revenue department for local requirements.

Learn more at IRS: Estate and Fiduciary Tax Forms

Probate is never simple, but it doesn’t have to be overwhelming.

Once you understand what’s required, who’s responsible, and how each step fits together, the process becomes much easier to manage.

Alix was designed to help executors stay organized, accurate, and compliant every step of the way.

Whether you’re just beginning or already partway through the process, we can guide you through forms, deadlines, and legal filings so nothing gets missed.

Probate

8min Read

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique.

Name Surname

September 2025

Probate

8min Read

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique.

Name Surname

September 2025

Probate

8min Read

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique.

Name Surname

September 2025